With the Second World War nearly over and peacetime reconversion already beginning, Toledo in July 1945 was a city straining under the weights of many problems.

In the space of twenty-five years, Toledo had been through a boom time of unprecedented growth, an economic depression that treated it and its residents cruelly, and World War II. As C. D. Innes put it in his book, Designing Modern America: Broadway to Main Street (Yale University Press, 2005, pp. 182-183):

Toledo – the third biggest port on the Great Lakes, a major automotive and aircraft manufacturing center and the world’s largest coal shipper – was suffering the all-too-familiar symptoms of urban blight in an extreme form. The twenty-four rail lines that converged there and made it a transport hub were strangling the city. Heavy industry blocked access to the Maumee River and covered surrounding neighborhoods with smoke and grime. In addition, since factories and warehouses were located upstream of the center, traffic across the river was continually stalled when bridges opened for ships to pass through, while the current carried all the smelly and dangerous chemical effluents down into the heart of the city. Homeowners and businesses had fled to the suburbs, leaving the city center in decay and crowded by low-income apartments.

Vehicular traffic was a huge problem. The city was beset with it from all sides, especially north-south traffic from Detroit. The Detroit-Toledo Expressway and the Ohio Turnpike were ten years off.

One particularly open sore was the city’s passenger railroad station. It was openly regarded as a disgrace. On June 10, 1930, a fire at the old Union Station gave hope that finally Toledo would have a modern facility (in fact, the News-Bee reported that people cheered at its burning). Instead, to everyone’s astonishment, the New York Central Railroad remodeled the damaged one. For years there was a billboard that urged visitors, “Don’t Judge Toledo By Its Union Station.”

Already, people were looking to the future. It was an old trend in Toledo, what with Jesup W. Scott urging great things for Toledo as the “Future Great City of the World” in the previous century. So, with the support of Blade Publisher Paul Block Jr., Toledo Tomorrow was born.

“It is the hope of The Blade that through Toledo Tomorrow the pride of the Toledoan in his city will be raised,” The Blade wrote, “and if that happens – ‘You can bet your life nothing will stop us,’ Mr. Block said.”

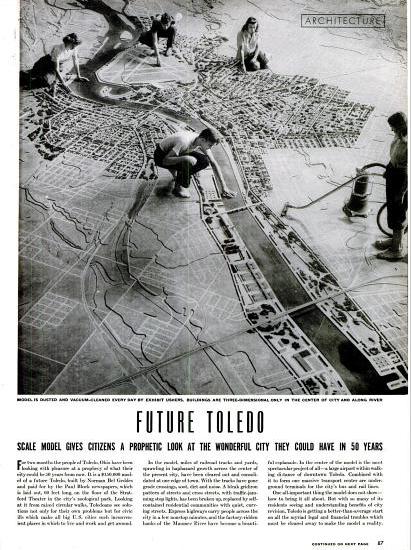

In its simplest terms, Toledo Tomorrow was a large, $150,000 scale model of a future Toledo that went on display July 4, 1945 at the Stratford Auditorium of the Toledo Zoo. But it was much more than that. It was part of an effort by The Blade and its publisher, Paul Block, who footed the bill for the exhibit, to give the city a push into the second half of the 20th century.

Even Mrs. Mabel Dunham Locke, wife of Robinson Locke, president and editor of The Blade from 1888 to 1920, attended the opening, along with a number of state and local officials.

The Blade asked this thought-provoking question:

What kind of city will Toledo be when today’s children are grown?

Toledo Tomorrow, with its huge scale model by Norman Bel Geddes, does not answer this question. The answer lies in the hearts and minds of the people of present day Toledo – the voters, the taxpayers, the engineers and the planners.

Toledo Tomorrow does depict the kind of city Toledo can be if its citizens hitch their wagon to a star and set out to transform their community.

Men and women now in their middle years can recall the transition from the horse-and-buggy age to the motorized world of today. As a city Toledo did not keep pace with that transition. It was patched here and there as it grew but fundamentally it did not change.

The community pattern that served Toledo in the quiet days of the 19th century is not adapted to the speed and bustle of modern life. Much less will it be adapted to the life scientists and engineers forsee in the near future.

Toledo Tomorrow is dedicated to the proposition that Toledo must reconstruct itself in the years that lie ahead so that it can enjoy to the full the spacious life made possible by advances in science, engineering and culture.

The centerpiece of Toledo Tomorrow was a sixty-foot scale model of the city designed by Norman Bel Geddes, who created the Futurama exhibit at the 1939 New York World’s Fair. Toledo Tomorrow emphasized transportation, which was not surprising, since Bel Geddes could arguably be called a visionary when it came to the subject.

Bel Geddes was from Adrian, Michigan and by all accounts knew Toledo well. His influence in modern design has been widely recognized. He wrote a book, Magic Motorways, that laid out a proposal for what eventually became today’s Interstate Highway System.

What was in the model? For one thing, (quoting The Blade again)

Toledo Tomorrow lies within and around a network of express highways, great arteries of motor traffic knifing through the heart of Toledo and affording safe, rapid passage to points in or beyond the city.

These highways are depressed below street levels or elevated above them so that there are no cross traffic or intersections. They are divided by landscaped center strips so that all danger of head-on collisions is removed.

Most of these highways carry eight lanes of traffic so that automobiles and trucks can move through downtown Toledo as fast as they can over rural highways.

And for the most part, this eventually happened, but without Toledo’s involvement (it was ultimately up to the State of Ohio to build the Ohio Turnpike and the state and federal governments to come up with the Detroit-Toledo Expressway).

The Bel Geddes plan perhaps over-emphasized air travel a little: it proposed five airports for the Toledo area: downtown, downriver, the Laskey/Jackman Road area, and by the Heather Downs Country Club on Glendale Avenue.

Rail travel was to be concentrated in one area southeast of the city, with through freight bypassing the city entirely.

From there, it was up to The Blade to assume a civic booster role and promote not only the show, but the ideas behind it.

Public reaction was positive, as reported in The Blade on July 6 and days afterwords as well, where an overline above the front-page masthead urged “Let us keep thinking about TOLEDO TOMORROW”.

The exhibit caught the attention of the nation, in newspapers as well as Life Magazine, which ran a large six-page spread on Toledo Tomorrow in its September 17, 1945 issue.

It was all forward thinking, and it was all good, but many of the ideas never came to pass. Trains still roll through Toledo every day, and the importance of air travel may (!) have been overemphasized in Toledo Tomorrow. Many of them did, however, and quickly: one of the major projects of the 1950s was a highway to funnel traffic coming south from Detroit to the new Ohio Turnpike.

The display stayed open until October 15, 1945. On that day, The Blade noted that plans for the new Union Station had been received.

Thirty-six years later in 1981, at a University of Toledo conference, Block said it was never intended as a master plan, but more as a boost, a way to get people thinking in a city that needed it.

“I conceived it as a stunt,” he said.

The story says the famous model was lost sometime after 1950. The book The Blade of Toledo: The First 150 Years, by John M. Harrison says the model was discarded about ten years later when storage and insurance made keeping it prohibitive.

The Toledo Lucas County’s Images In Time website has a number of pictures of Toledo Tomorrow, which is where I got the highlighted photo.

my brother and i were just talking abput the exhibit and how i could remember being held up so i could see it. my brother assumed the exhibit was somewhere on exhibit. too bad it has been lost.